HIMALANA – FAIRLY TRADED WOOL FROM THE ROOF OF THE WORLD

Zwei Jahre hat es gedauert bis aus einer wilden Idee Wirklichkeit wurde: 6000 Schafe, die ihre Sommer auf Hochweiden im Himalaya nahe der Grenze zu Tibet verbringen, sind jetzt biozertifiziert. Von diesen Schafen stammt Himalana, die erste biozertifizierte und fair gehandelte Wolle vom „Dach der Welt“.

The Himalana wool project combines in one outstanding product organic certification and Fair Trade, environmental protection and the sound economics of a traditional life. The Himalana sheep are a breed that supplies different types of wool of an excellent quality. Himalana wool is extremely versatile and can be used for a wide range of products from clothing to carpets.

What started as a pilot project in the Indian Sangla Valley has now been extended to the neighbouring Rohru valley: another 24,000 sheep are now certified organic and their proud owners and herders can market the Himalana wool under Fair Trade conditions.

PROJECT HIMALANA

Who comes up with the idea to set up a Fair Trade scheme and get thousands of sheep in a remote valley in the Indian Himalayas certified organic?

Two Swabians and an Indian: Norbert Baldauf, Martin Kunz and Sushanto Mittra.

On the following pages we'll tell you how the project works and who benefits. Among the latter are Indian weavers who are already producing beautiful carpets out of Himalana wool – under Fair Trade conditions, naturally.

Norbert Baldauf is the founder of PROLANA, a company that produces natural bedding and mattresses. Organic and Fair Trade have been important principles since the start of the company in 1987. Norbert is fascinated by the fantastic qualities of wool which he came to know about as co-founder of a shepherds' cooperative. That's why if need be he can still sheer a sheep.

Dr. Martin Kunz is a Fair Trade pioneer. He is one of the co-founders of the original international Fairtrade logo TransFair, he was the first secretary general of Transfair International, the predecessor of FLO (Martin was also FLO's first CEO). Developing Fair Trade concepts – sometimes in far flung corners of the world, for people with very different living and working conditions and a variety of very different products – and setting up Fair Trade supply chains is what he still does. He knows and loves India since he first came to Calcutta in the 1970s and stayed for a year and a half, working in social projects there.

Sushanto Mittra studied economics and is so good at making nifty stuff that actually works that he could be considered an honorary Swabian. Development, production and marketing of wooden toys (for the European market) and folding furniture (for the Indian market) are two of his long-standing projects. And remembering the months he spent with small scale farmers in Mizoram, one of the smallest and most remote states in the eastern most region of India, still gets a dreamy, longing look onto his face. Helping farmers with organic certification and finding a market for their products is a job he loves doing.

Like Norbert and Martin Sushanto is convinced that people's living and working conditions can be changed for the better through Fair Trade. All three also believe that organic agriculture and animal husbandry are good news for farmers, consumers and the environment. And they share the concern regarding the future of fragile ecological regions like the high meadows and forests in the Himalayas. That's when things suddenly started to come together for them: those summer meadows, the sheep and their herders, wool, organic certification and Fair Trade.... Project Himalana was born.

THE SANGLA VALLEY - WHERE HIMALANA SHEEP GRAZE

The Sangla Valley is the first region in India with herds of certified organic sheep. The remote mountain valley is situated in the Indian Himalayas close to the Tibetan border. It took two years of hard work at altitudes of up to 5000 m to complete the certification process. Today sheep owners and herders are proud to be the first in India to produce pure new certified organic sheep's wool.

Tiny white dots moving slowly across the expanse of a mountain pasture, that's all you can see from a distance with the naked eye. Only once you leave the dirt road and start climbing up the steep mountain slope you can make out the hundreds of sheep with their lambs and some goats, too. Two huge, reddish-brown sheep dogs watch the herd attentively. The herders have time to brew tea over a small wood fire – they drink it which they have with fresh goat's milk and salt.

The summer pasture for this organic certified Himalana herd is situated at the end of the Sangla Valley at an altitude of about 4,000 m. It takes the herders four hours on foot to get to the nearest village, Chitkul, the last outpost of civilization this side of the border. Even though the air lacks oxygen at this altitude the men are able to walk extremely fast. The most remote summer pastures are located at altitudes of up to 5,000 m, surrounded by solitude and the snow capped peaks of the Himalayan mountain ranges. Somewhere here is the border to China and Tibet and the nearest Indian village is at least a day's journey away.

At this elevation the nights are cold even in summer but their thick coat keeps the sheep warm. From middle of September the herds make their long way to the winter pastures in lower lying, warmer valleys. Before they start their trek down the mountains the sheep are sheered and the result is the Himalana wool.

Herd, herders and dogs descend from the high mountain valleys using mule tracks. They pass Chitkul, a village with traditional wooden houses adorned with beautiful carvings. Buddhist flags fly in front of the temple with its wooden columns, entwined by long tailed dragons. Tibet is close. Now, at the beginning of September, the villagers bring in the hay that will feed the cows over winter. Chitkul will be snowed in for several months and at times totally cut off from the rest of the world.

As the herds get closer to the lower end of the Sangla Valley the landscape changes: sheltered from the worst of the cold and too much rain by high mountains and steep rock faces, apricot and almond trees grow. The changing climate has apple trees flourishing at an altitude of 3000 m. Apart from sheep farming the orchards are the most important source of income for the farmers in the valley.

The economy in the Sangla communities has only picked up since the valley has become accessible by road. Picture a single lane, potholed track, with hairpin bends, sometimes blasted into the vertical rock face or crumbling on the edges, too narrow for two cars to pass each other except at special laybys. Now it's a three hour drive to Peo, the district capital, where farmers sell produce like fruit and peas and where they bring wool for processing. And of course all essential goods needed in the valley, from cooking oil to building materials like cement or bricks, all has to be brought up this treacherously narrow road that often leaves no more than a hand's width of space between the tires and the abyss.

To get to the plains, some 350 km to the south takes at least two days by car – along endlessly winding roads and across dozens of mountain passes. The Himalana sheep, the herders and their dogs cover the same distance to get to the allocated winter pastures. On average it takes eight weeks to complete the journey from the summer pastures in the Sangla Valley to the low lying winter pastures in Nahan. Until the end of April the sheep will stay on the pastures in the open, government managed forests. After another sheering they will again set off and it will be June until they reach the mountain pastures at the roof of the world.

OF HERDERS AND THEIR SHEEP

There is the odd black sheep amongst the Himalana flock, as are brown, grey and mottled ones, but the majority is white. All have large, expressive eyes, ears that prick up as soon as you come near them or hang floppily when there is nothing to focus on but grazing. The sheep are crossbreds and show characteristics of two breeds: for one the dense, long and soft coat which is typical for Rambouillet Merinos. This breed originally came from Spain, in the 18th century it was bread at the royal farm at Rambouillet near Paris and later exported the world over. But their sturdiness, robust health, strength and energy the Himalana sheep owe to their maternal line, a local breed called Rampur Bushair. It's down to each sheep's ancestry whether it's wool will be wonderfully soft and perfect to be woven into a fabric perfect for a tailored suit or whether the wool has lots of crimp and is ideal for making carpets. The secret is in the sorting when sheering.

Sheep farming has a long tradition in India, wool is essential if you want to survive the harsh winters in the mountain valleys of the Himalayas: there isn't any other material that keeps you quite as warm while protecting you from wind and snow. The herders still wear thick woollen jackets and trousers and no bride would marry without a woven stole adorned with a wide, colourful border. A family in the Sangla Valley requires about 50 kg of wool per year – the wool of 30 sheep – for their own needs.

The highest mountain pastures are at an altitude of about 5000 m, here the first snow might fall by the middle of September, it's likely to keep the grass covered for the next six months. The sheep spend the winter months on low lying pastures several hundred kilometres to the south. The winter pastures are in open, government managed forests. Over time the forest department and the sheep owners have set up an intricate, strictly controlled system for the migration of the sheep and the allocation of pastures.

Summer and winter pastures are precisely mapped, as are the long migration routes. All sheep owners are registered, as are their sheep - the rams even have their picture taken. The forest department works out the migratory routes for the herds and allocates the winter pastures. The system is well documented and strictly controlled.

In each village one or two owners take on the task of organising the sheep and goats of different owners into joint herds called tolis. Some owners have 50 or 60 sheep, others several hundred. A toli or herd is 600 to 900 animals strong. Depending on the size more or fewer herders have to be employed to look after the sheep over the summer and winter season. To organise when and where their sheep are sheered is the responsibility of the individual owners.

The herders stay with the sheep on the pastures and manage the long migratory journeys – not an easy task: the paths the sheep take have to stay clear as far as possible from orchards, fields and gardens, young lambs have to be carried. En route there may be sheep rustlers or predatory wild animals like panthers and bears. Large brown sheep dogs help keep the herd together and if the going is slow the goats are put in front – they walk at a faster clip and set the tempo for the rest of the animals. For this difficult and demanding job the herders are paid with a number of sheep which they will keep with the rest of the herd during the next season.

THE PAINS AND JOYS OF OUTDOOR MOUNTAIN LIFE – MEET THE HERDERS

It's late morning, Danraj Pistan squats in front of a small wood fire and makes tea with fresh goat's milk and salt - for anyone not from the region the taste may take some getting used to. A blue tarpaulin draped over a washing line and anchored with some stones offers protection from the wind.

Sechs Schäfer schlafen nachts unter diesem Behelfszelt, dazu ein halbes Dutzend Ziegenbabys, die es regelmäßig schaffen, einen weichen Liegeplatz zu finden. ‚Ein oder zwei haben wir ganz gern mit im Zelt‘, lacht Danraj,‚sie halten wunderbar warm‘. Die Herde (Toli) die er gemeinsam mit den anderen Schäfern hütet umfasst 1500 Tiere, 900 Schafe, der Rest sind Ziegen.

The lambs stay close to their mums, kit goats get to play together in a kind of kindergarten so that their mothers can be millked.

Mr Pistan, aged 45, is one of the oldest and most experienced herders in the group. He's been herding sheep in the Sangla Valley for 25 years. Like most herders in Sangla he originally comes fro the neighbouring Rohru Valley. What looks like a short distance on a map turns out in reality to be a foreboding, snow capped mountain range.

There is only one access by road to the Rohru Valley and that road is in a neighbouring state – a detour of 500 km. The remoteness of the valley has led to economic deprivation. Apart from subsistence agriculture there are very few other sources of income which is why many men come to Sangla as herders. They usually get one month(?) off in a year and that's the only time they have a chance to see their families.

Danraj Pistan left school after five years at the age of 11. The family owns about half a hectare of land. The women grow vegetables and look after some 35 apple trees owned by them; Danrajs father, too, was a herder. While staying on the summer and winter pastures the herders move camp about once a week. Life seems unhurried compared to the three to five months they spend on the road migrating the sheep.

The tarpaulin, a blanket, a pressure cooker that works on a wood fire to make Dal (lentils, spiced with coriander and cumin, eaten with rice or flat breads), some kitchen utensils made from steel and a few provisions – that's it. Herders travel light because everything needs to be carried, either by the goats or by the men themselves. Few herders own a mule to help with transport.

Every few days one of the men has to go to the next village to get supplies. 'Right now we are not far from Chikul', says Danraj, that's only four hours away - on foot.... The herders rotate tasks. Looking after the kit goats is not one of Danraj's favourite jobs, he prefers to be with the sheep on remote pastures, that kind of work comes with a lot more responsibility and Danraj can draw more on his experience and skills.

Herders like Danraj know each animal, they see immediately when a ewe is lame or a lamb doesn't feed. Government veterinarians working out of one of the many field stations in the region support the herders. The vets are familiar with the principles or organic management practices and they are ready to assist and advise. Occasionally the herders have to act as midwives too, there are always some sheep who give birth during the long migration. The mums will be up on their feet and walking just minutes after giving birth, but their lambs will have to be carried by the herders for the rest of the way.

Chitkul is the last village of the Sangla Valley. Only a narrow dirt road leads further up into the mountains and towards the border with China and Tibet. While several herds graze on the steep mountain slopes one of the herders sits by the road side, next to him three large sacks full of wool. He owns a number of sheep who run with the toli he works for and the wool in the sacks comes from his sheep whom he has just sheered. He will sell about half of it, the rest will be needed by the family. Raijun is 51 and, like Danraj, he's from the Rohru Valley.

In a few weeks the long journey to the winter pastures will start. Once the herd reaches he will sell off half of his sheep. The money from the sale will have to cover most of the families expenses for a year. The school fees for his older son who studies at a college in the town of Rohru amount to Rs 50.000, about Euro 670. His younger son will graduate soon, his daughter is six years old and has just started school. He hopes all this children will study and choose a career, he wants none of them to become a herder. His family owns a small plot of land with an apple orchard.

The money they make from the apples also contributes to the children's education. Raijun is happy to soon be leaving the mountain valley, at night the temperatures already drop to freezing. Nights on the low lying winter pastures will be warmer, but working with the sheep becomes more difficult. They have to be kept closer together and supervised all the time, the vegetable gardens of nearby villages are beckoning ...

There is no such thing as a night of uninterrupted sleep anyway. Throughout the night two herders have to keep watch in a three hour shift pattern. Trees grow to an altitude of 4000 m and predators like panthers and bears live in the forests. 'The night before last a panther attacked the herd', says Danraj who works with a different herd, 'we managed to chase him away with shouting and throwing stones.'

On the long trek through the forests en route to the winter pastures such attacks are even more frequent. For the duration of the journey the dogs wear wide steel collars with spikes on the outside, it gives them a chance to survive when a panther or bear tries to kill them. 'It is very scary', says Danraj, 'but to protect the animals is part of my job'.

HIMALANA AND FAIR TRADE

The Himalana project for certified organic pure new sheep's wool in the high mountain valleys of the Indian Himalayas is unique and the first of its kind. From the start one of the goals was to put in place a Fair Trade arrangement that would help improve the living and working conditions of sheep owners, herders and their families.

Producers of Himalana wool get a consistently better price for their wool. And it is up to them to decide what project should be funded through that extra income.

One example is the life insurance scheme. Himalana sheep owners and herders opted for the contributions to be paid through the Fair Trade premium. Sheep farming and herding in the high altitude mountain ranges of the Himalayas is dangerous. Everyone here is worried about how their families would survive if the main bread winner – a sheep owner or herder – were to die prematurely. To have a life insurance provides at least some financial help.

The life insurance scheme is organized in co-operation with the UCO bank in Rakcham, the last banking facility before Chitkul. To get cover the herders first have to open an account. Sheep owners usually already have one. Opening an account is easy enough, says the deputy manager Nilesh Kumar, all you need is a photo ID and a permanent address.

Mr Kumar agrees to employ a new 'banking correspondent', a type of job that has been introduced in India only in recent years and usually is done part time. The banking correspondent is equipped with a small gadget, similar to a hand held card reader, that works with a finger print rather than a personal security code. Service hours and a location are agreed in accordance with the needs and availability of the customers. Nilesh Kumar will look for a banking correspondent in Chitkul, a village about 10 km further up the valley, who will even make his way out to the distant high altitude summer pastures. The herders can withdraw and pay in money and the banking correspondent receives a 10 Rs commission for every transaction, an incentive to provide good service and recruit new customers.

Once they have opened an account the herders receive a cheque book and a cheque card. In very remote areas transactions can be done via mobile phone. The fact that having a bank account is a necessary precondition for getting life insurance cover is a very positive development. Up to now the herders had to carry large sums of money to buy provisions when they were migrating the sheep to the winter or summer pasture.

Now the sheep owners can transfer the money into the account of the herder which makes them a less likely target for robbers. And fraudsters don't stand much of a chance either. One of the Himalana herders, Danraj Pistan, lost all his savings when he handed it over to men pretending to be banking agents. With an account and the finger print reader, the genuine banking correspondents make such fraud impossible.

And once the herders have kept their account for a year without running into problems they can apply for a credit at regular bank interest rates rather than the exorbitant ones of private lenders. Especially in an emergency, for example in case of death, injury or serious illness, families are often forced to borrow money from such private money lenders who charge annual interest rates of 300 % and more. The life insurance scheme for the Himalana sheep owners and herders is a perfect start for a Himalana Fair Trade project.

DIMPLE NEGI – HIMALANA SHEEP START A TREND FOR ORGANIC

The room on the first floor of the spacious wooden house is painted in pink and light blue and furnished to accommodate a large number of guests. Dimple sits in one of the many armchairs and smiles. Her father in law of course knows much more about sheep and how to organise a joint herd (or toli), she says, but yes, it is true, for the last three years she's been in charge of doing this job in her village.

The family owns 600 sheep and goats, but the herd Dimple has to manage consists of 1,800 animals owned by 16 families. Some own just a few sheep, others several hundred.

The Negis and the other sheep owner of this herd live in Batserie, a beautiful village in the middle of the Sangla Valley and surrounded by fruit orchards. To manage a toli is a demanding and a big responsibility. It's an unpaid position but to be chosen for this job means having the respect and trust of the community. At the start of the season Dimple has to employ the herders and negotiate the terms of their employment. Most of the herders apply year after year to be working for her and Dimple wants the men to like what they do, 'when the herders are content they will look after the animals better'.

Seven shepherds look after the herd, all of them come form the remote Rohru Valley. The men get four months leave in a year, two months in spring and two in autumn – much more generous terms than they would find with other herds. The pay is better too.

Throughout the season Dimple has to make sure that the herders get their provisions or have enough money to buy them. One of the herders has arrived in the village the night before to collect food and supplies: rice, spices, lentils and vegetables from Dimple's garden. The herder will rest for a day and then get back to his colleagues and the herd – eight hours on foot, carrying the provisions.

At the end of the season Dimple will add up the costs for wages, provision and equipment like blankets. The sum then has to be divided between the families depending on how many sheep they have in the toli – the more sheep they own in the herd, the more they will have to pay towards the expenses.

Listening to Dimple talking about the herders it becomes clear that she knows full well, how hard and difficult the work is these men do. She thinks it's a great idea that the contributions towards life insurance are paid through the Himalana Fair Trade scheme. She knows how fast families can get into a desperate situation – she has a list with the telephone numbers of the families of all the herders that work for her. And the families know how to reach Dimple. In case of an emergency she can be relied upon to pass messages on between herders and their family.

It would make sense to get better tents for the herders and light weight solar lamps – Dimple says she would love to work with Himalan to improve the living and working conditions of the herders. When she is not busy with the herd or looking after her nine months old twins she teaches at the local school in Batserie. She would have liked to become a lecturer for history at a college in Shimla (the famous summer residence of the government during the Raj).

But while at uni in Shimla she fell in love with a fellow student and after the wedding both moved back to the Sangla Valley. She enjoys the time she has with her sons, particularly as in three and a half years from now they will start attending a prep school in Shimla, a ten hour drive away. Only in Shimla can you find a really good school, says Dimple. And a good education is a priority, everyone in the family agrees on that, even if it means that parents and children hardly see each other throughout the year.

And Dimple cares deeply about the food the family eats. The family's wood clad house is adorned with rich carvings and behind it is a large garden with a vegetable plot big enough to grow practically all the vegetables the family needs. None of it is ever sprayed with pesticides or treated with chemical fertiliser. 'Organic vegetables are good for all of us', says Dimple.

And when she saw how the organic certification of the Himalana sheep was achieved, she decided to get 'into organic' herself: The 100 young apple trees that have been planted on part of the Negi's land this year will be managed organically from the start. 'Right now there is not much demand for organic fruit yet' but in hotels and restaurants in Shimla organic produce starts to be available on a regular basis. 'In seven or eight years time when these trees start to produce fruit a lot of customers will have understood that organic fruit and vegetables are healthier for them, for the farmers and for the environment.'

JAWAHARLAL THAKUR – OF LIFE IN THIN AIR AND THROUGH LONG WINTER MONTHS

Chitkul is situated at an altitude of 3,450 m at the top end of the Sangla Valley, beyond Chitkul there is only a narrow dirt road that leads through rugged terrain towards the snow capped mountain ranges and the border with China. Steep paths and steps connect the old, often beautifully adorned wooden houses, several temples and numerous small elevated storage facilities. Now, in autumn, they are filled to the brim with hay and fodder to get the animals through the winter.

Jawaharlal Thakur's house, too, is built in the traditional style: via stairs on the side of the house one enters a long, wide corridor on the first floor with two rooms and the kitchen going off to one side. Through the windows on the other side one has a magnificent view towards the end of the valley and the snow covered mountains.

The wood panelled ceilings and walls in the living room and the many colourful woven blankets and cushion covers seem almost similar in style to old farmhouses in the European Alps. With 1,500 sheep Thakur's herd is one of the largest in Chitkul. Together with his wife Sarina Devi Jawaharlal also farms 1.5 ha of land. They grow vegetables for their own consumptions and peas which do very well in this part of the Sangla Valley and are renowned across northern India for their particularly good taste.

After the peas have been harvested the plants are cut by hand as fodder. Now, in autumn farmers put huge bundles of pea greens just about everywhere to dry them off: they hang from trees, are draped over fences and spread out on walls. Lower down the valley the Thakurs own another plot of land with about 100 apple trees. Up in Chitkul the climate is (not yet) mild enough to grow fruit. Jawaharlal never thought he'd become a farmer.

Jarwahalal was just 25 when his father suddenly died and he was the only one living in Chitkul and able to take over the farm. Both his older brothers were away studying at the time, today one is a lecturer for geology, the other one is a civil servant. Only Jawaharlal's youngest brother is still in Chitkul, too, he's running a small restaurant and a shop. Over the summer months his best customers are the herders who come regularly to buy provisions.

Jawaharlal Thakur employs nine herders. With lambing September is one of the busiest months of the year for everyone. He expects 250 lambs to be born, says Jawaharlal. And before the sheep go on to the long trek to the winter pastures they have to be sheered. It's a strenuous time for the herders and for Sarina Devi who every night has to cook a warm meal for everyone.

Right now it's still warm during the day but from middle of September Chitkul can get the first snow. From January to April the village is often completely cut off from the rest of the world. Even the snow ploughs operated by the army usually need several days until they have cleared the only road leading into Chitkul.

The villagers are used to living through these harsh winters, but if there is a medical emergency, a life threatening scenario can develop quickly. 'We have an ayurvedic doctor (trained in traditional Indian medicine) here in the village, but no midwife', says Jawaharlal. He still remembers 27th February, 2015. 'Our neighbour was highly pregnant. The baby was in a breech position and we knew that we had to get her to the doctor in Rakcham'. It's the next villages, just 10 km down into the valley.

The men first cleared a track and then carried the neighbour on a stretcher. She delivered a dead baby while they were on the road to Rakcham, but at least her life could be saved. The Thakurs have two children, nine year old Sidarth and 13-year old Prinan. Both live with Jawaharlal's brother in Solan, 300 km away because only there can they attend an English medium school. 'We talk on the phone a couple of times a day' says Saina Devi.

Being separated is hard on everyone but getting a good education comes first, both parents agree on that. The children should have a chance to get into any profession they chose. 'They will have a family of their own, we'll see where they will settle', says Jawaharlal. 'One day they will return to Chitkul. This is where their roots are.'

BALDEV SINGH – OUR LIVELIHOOD DEPENDS ON SHEEP

Baldev Singh wears the traditional grey woollen felt cap with a green velvet border which is typical for the Sangla Valley, his trousers and jacket too are made from wool. His wife has spun the yarn, a weaver in his village has woven the cloths and naturally the wool comes from his own sheep.

The family needs 50 kg of wool per year, it's the wool of about 30 sheep. From the yarn clothes are made for Baldev Singh, his wife and the four children, and they need shawls and blankets. Mr Singh owns 500 sheep which are sheered in the first week of September.

Through the course of the year the sheep of several owners are combined to one big herd, called a toli, but when and where his animals are sheered is the decision of each individual owner as is planning and organising it. Baldev Singh has a regular spot set up to do the sheering. It's situated half way between his home village, Rakcham and Chitkul at the upper end of the Sangla Valley. The sheep wait together with some goats in a walled enclosure. Goats are part of every herd: they supply fresh milk, carry loads and if there is something to celebrate one of them is likely to become the nicely roasted centre piece of the feast. But goats are not sheered. The sheep wait patiently and don't seem nervous until one of the helpers grabs them by their hind legs and drags them to one of three sheerers. This year for some of the sheep sheering will be over before they properly know what's happening. A German non governmental organisation has sponsored two electrical sheering knives and with those the sheerers take just a third of the time to free each sheep from its heavy woollen coat. The electrical sheering knives look a bit like the outsized version of the gadget hairdressers use to clean the back of the neck of their short haired human customers. Using the electrical knives the sheering is more even and the quality of the wool is improved. And it's less strenuous for the sheerers. It takes strength to sheer a sheep with traditional scissors and usually the men get large blisters on their hands within a few hours of working. By the way: regular sheering is necessary to maintain the health of the sheep and part of their care. If left to grow the sheep would hardly be able to move and prone to get ill.

The sheering knives are operated from a car battery. Himalana has contributed to the financing of a solar panel, the battery can now be charged continuously and in an environmentally friendly manner. Baldev Singh is happy to work with Himalana. Before this co-operation the buyers came to where sheering was taking place, bought as much as they needed leaving the rest for the farmers to sell to government agents at very low prices.

Himalana guarantees to buy fixed amounts of wool, provides sacks for the transport of the sorted wool and pays a good price. This way Himalana can guarantee a high wool quality while treating producers fairly. Like most other sheep owners Baldev Singh has an additional income through some 50 or so apple trees. But the sheep are his main source of income. 'The sheep are our livelihood, our existence depends on them' he says, without woollen clothes and blankets it would be impossible to survive the long Sangla Valley winters. 'And only by selling wool are we able to make enough money to live.'

HIMALANA – FAIRLY TRADED WOOL FROM THE ROOF OF THE WORLD ...

... AND WHAT YOU CAN DO WITH IT.

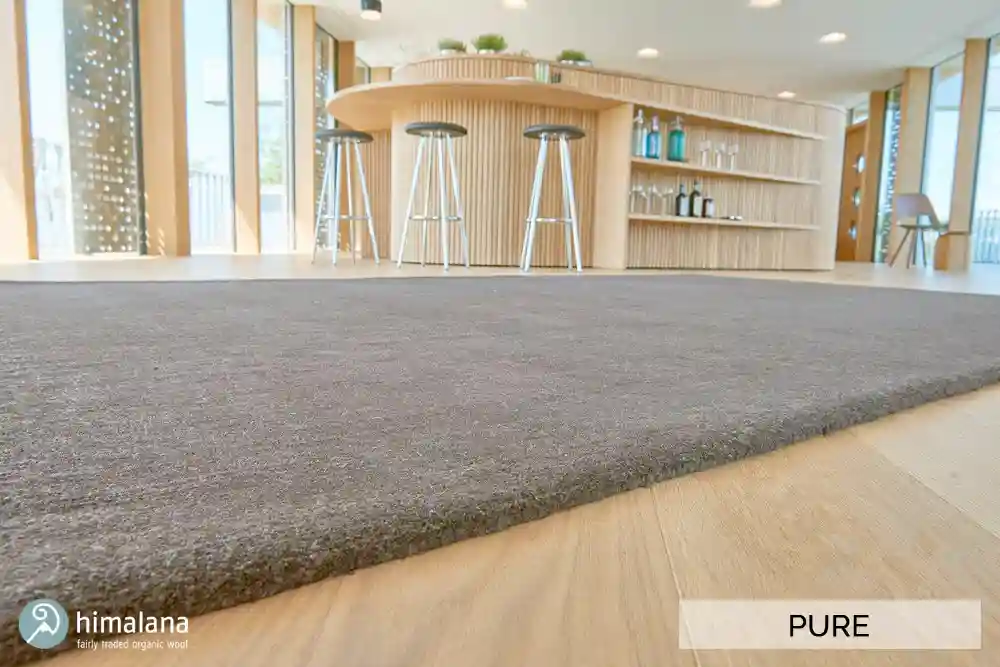

Even at an altitude of 5,000 m, in summer it can get hot on the mountain pastures of the Himalayas, at least during the day. At night temperatures can drop dramatically. Sheep are ideally suited to deal with such temperature changes. Sheep's wool has a structure that allows the fibres to absorb a third of their weight in moisture and to quickly release it to the surrounding air – the woollen coat has temperature regulating properties which prevent the sheep from getting too hot. The crimp of the wool gives the sheep's coat the properties of an air buffer, providing insulation against the cold when temperatures drop. Pure new sheep's wool retains these properties which is why it is such a wonderful and versatile material for clothes – from suits to pullovers, from scarves to socks, and its also an excellent filling material for duvets and pillows, it can be used to insulate wall cavities, maintain the temperature of produce like meat or dairy during transport or to make carpets with. Himalana has made a start with the latter: in co-operation with the non governmental organisation Unnayan Indian weavers make carpets from Himalana wool – under Fair Trade conditions of course.

From the roof of the world into your living room – Fairly Traded carpets made from Himalana wool

Pure new sheep's wool has very special properties: it is temperature regulating and soft but also durable and easy to care for. Wool is ideal for making carpets. Himalana wool carpets are produced in a particularly disadvantaged region in the eastern part of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.

Für die Teppiche aus Himalana Wolle arbeitet das Himalana Team deshalb mit der indischen Nichtregierungsorganisation Unnayan zusammen. ‚Vor 18 Jahren habe ich zum ersten Mal versucht, zusammen mit Unnayan ein Fair Handelskonzept für die Teppichweberinnen und Knüpfer aufzubauen und einen Absatzmarkt in Europa zu schaffen. Wir sind damals weit gekommen, aber letztlich sind wir an einer mangelnden Nachfrage gescheitert,‘ sagt Dr. Martin Kunz, der Fair Trade Spezialist im Himalana Team. ‚Mit Himalana Wolle eröffnen sich v.a. dank Norbert Baldauf von Prolana ganz neue Möglichkeiten und gerade bei den sozial und wirtschaftlich extrem benachteiligten Teppichweberinnen läßt sich mit einem Fair Trade Projekt wirklich etwas bewirken. Dass es nach so langer Zeit nun doch mit den Fair Trade Teppichen geklappt hat, das freut mich wirklich‘.

CONFIDENT, COMPETENT AND WITH THEIR OWN INCOME – UNNAYAN WOMEN WEAVERS

Gracefully Vijaya Rai hops off the back of the motorbike. She is a petite woman clad in a simple sari. Her voice is soft but becomes intense when she starts talking about Unnayan and the women carpet weavers. The centre of Indian carpet weaving lies about 50 km east of Varanasi, the holy city on the banks of the Ganges. Mrs Rai knows the region around the cities of Mirzapur and Bhadhoi well, she grew up in a village outside of Varanasi. She is the founder of Unnayan, an organisation that aims to create income opportunities particularly for women.

Vijaya Rai knows about the extreme poverty and desperation in this part of Uttar Pradesh, one of India's most populous states. The land is fertile, here in the flood plains of the river Ganges, but it is all in the hands of just a few feudal landlords, the majority of families are landless. There are some jobs to be had in quarries and of course in the carpet industry, but most men work as day labourers and in particular young people move to the slums in India's mega cities in search of work.

Vijaya Rai and her husband founded Unnayan in 1994. Carpet making has a long tradition in India and it creates employment opportunities for women: they can work from home and have flexible hours which allow them to look after the children, do housework and still earn some money.

Unnayan set up women's groups which (after a six months training period) took on joint responsibility for one loom each. 'Until 2000 we had some really good years', says Mrs Rai, 'some families already had a loom, others were able to buy one. More than 150 women had a regular income through carpet weaving.' But then the orders from Europe stopped coming. 'We just didn't have a reliable partner', says Vijaya. Today that's different.

The raw material for the carpets is organic certified, Fairly traded Himalana wool. Unnayan guarantees the fair remuneration of the weavers. The organisation also provides training and advice to make sure you receive a perfect carpet made from Himalana wool.

FURTHER ASSORTMENTS FROM HIMALANA

Upholstery fabrics Wool / Silk GOTS

In addition to GOTS sheep's wool we have also developed GOTS wild silk as part of our organization and infrastructure of the Himalana project. This combination creates one of the highest quality upholstery fabrics available in GOTS quality with wool and silk.

Yoga mats – GOTS & FSC

Our yoga mats have a GOTS certified Himalana wool felt surface. The bottom is made of a FSC and Fair Rubber certified natural latex coating. This prevents the yoga mat from slipping on the floor and thus offers secure grip at all times.

THE ORDER FOR A CARPET MAY ENSURE SURVIVAL ... MOHAMED HAROON AND HIS FAMILY

Steep, uneven steps lead up to the house of the Haroon's and a small workshop. Together with other Muslim families they live on the far side of the village. As for the Haroon's: eleven family members share two of the rooms, the third is needed to store the wool.

Several women are squatting in the neat courtyard amidst piles of wool. They sort it by colour and prepare the shuttles. Next door, set up in the open are eight looms protected from sun and rain by a corrugated iron roof. The frames are sitting on the ground over a pit which holds the pedals needed to operate the loom. This setup allows the weavers to sit more comfortably while they work.

Mohamed Haroon founded the workshop but now his oldest son, 30-year old Mohamed Iqram has taken on the day to day tasks. No one in the family ever had the chance to attend school regularly and learn how to read and write. But everyone certainly knows how to work with numbers, within no time they have transposed the drawing of a complicated design for a carpet into the settings needed to replicate it on the loom. Right now the family has enough orders to guarantee a monthly income between 12 – 15,000 RS, about 160 to 200 Euros.

On the other side of the house, Mohamed Iqram's wife Shana Begum is preparing a simple meal for the family over an open fire: dal – lentils cooked with spices – and rice. Here two and a half year old daughter Mumtazar is playing at her side. Mumtazar, too, will some day weave carpets, says her father. The family owns four goats but no land.

Mohamed Iqram has thought about going to one of the big cities like Delhi in order to try and find work there, but he didn't want to leave his elderly father and siblings behind, he says.

Does he have dreams of what the future might look like? He shakes his head. 'I can't think about that', everything depends on whether we have any money. It's not just the question of how we live, it's the question of whether we live.'

In co-operation with Himalana, Unnayan makes sure that families like the Haroons receive a fair wage for their labour. And with enough orders Mohamed Iqram's dream might come true after all: his siblings, three sisters and two brothers, could get married and have families of their own.

OF CARPETS, TRAVEL PLANS AND THE POWER OF THE SISTERHOOD ... MUNI BEGUM AND HER DAUGHTERS

A tiled roof protects the two looms at the side of the house from the elements. That's where Muni Begum and her daughter work. Over their banter and laughter you barely notice the rhythmic clacking of the loom.

Next to them on the bench sits 17 year old Jahanara, the youngest of seven children. The women are wrapped up warmly in shawls and scarves, in January it gets cold in northern India, temperatures can drop to below freezing at night.

Muni Begum's husband is a day labourer in the construction industry and earns the equivalent of about 80 Euros a months. Their eldest son moved to Mumbai with his family a few years ago and regularly sends money to his parents, usually about 80 Euros.

In 2002 Muni Begum was one of the first women in the village who started working with Unnayan. Until then she'd been 'in purdah', which means she barely left the house and if she did she would be veiled from head to toe. 'I certainly would have allowed a man to take my picture', she says, smiling into the camera. At Unnayan she learnt that women have rights, she says, women can work and earn money, they can take decisions, travel and talk with whom ever they want.

With their two looms mother and daughter at present earn about 40 Euros per month. Her husband is ok with the fact that she is working, says Muni Begum, and the family really can do with the extra income.

In 2014 Farida Bano, her mother and other Unnayan women travelled to Delhi to take part in a women's conference. They took a whole bundle of hand woven shawls and sold them at a fair. It was such a fantastic trip, says Muni Begum, who just loved being in Delhi. We could go everywhere, no one cared what we were up to, not like here where everyone always knows every one else's business.

Farida Bano and her sister Jahanara have both gone to school. Both want to get married eventually, but they want to work and earn money, too. Begum Muni got married when she was 14, that's way too early, she says and before her daughters get married she wants them to learn a trade, like weaving carpets. 'My dream is to set up a women's group', Farida Bano chips in, 'we would weave and embroider shawls and every few months we'd go to Calcutta or Delhi and sell them'.

Her mother has even bigger plans: If she got enough orders to do Himalana carpets and could save some money, she would set up a proper workshop in which very delicate woollen shawls could be made, too. 'We'd be able to do everything, from a carpet to a stole'.

WHERE EVERY RUPEE COUNTS... LONG DAYS AT THE LOOM: ANJU

Anju's enormous loom takes up most of the space in the courtyard. Her house is at the centre of the village. While Anju is working her youngest daughter, four year old Kanchan, plays next to her, she is the youngest of six daughters. Tied to the wooden gate stands Munmun, Kanchan's pet goat. The animal is wearing a red sweater against the January cold.

With its flowering creepers and numerous pot plants the courtyard seems almost idyllic. But Anju works at the loom for 10 hours a day, from ten in the morning until eight at night. Even as she is talking to us she hardly looks up, the piece she is weaving just has to be ready on time.

Despite her long hours at the loom Anju only earns about 2,000 Rs per month, the equivalent of about 30 Euros. Like many weavers she gets the orders from subcontractors who know that people like Anju are so poor, they need to work whatever the pay. Weavers like her often receive only a fraction of the legal minimum wage.

Anju needs every rupee. Her husband owns a small cart from which he sells clothes. Even in a good month he doesn't bring home much money and in a bad one Anju hardly knows how to feed the family. Four daughters still live at home, and (except for little Kanchan) all got to school. In the afternoon they do the house work and cook, Anju hasn't got the time to do either. She doesn't want her daughters to learn how to weave, says Anju, she hopes they all will find husbands who earn enough money to support their families.

Her two oldest daughters are married and live in villages nearby. And of the girls still living at home none should have wedding plans any time soon: marrying off a daughter costs money. And money is what Anju and her husband haven't got.

Does Anju have dreams? What are her hopes for her daughters? 'Just don't ask', she replies, 'with what I'm earning it's better to not even thinking about such things'. Maybe she's right. So far it's unclear whether there will be enough Himalana orders to provide work for all the Unnayan weavers. But the women who will weave Himalana wool carpets will receive a fair wage: it will be the legal minimum wage plus an additional 15% Fair Trade premium.

KONTAKT & IMPRESSUM

Diversity Honeys Ltd.

83a Mill Hill Road

London W3 8JF, UK

E-Mail: info@diversityhoneys.

Telephone: +44 7879131550

Director: Dr Martin Kunz

Company Incorporation Number: 09972897

VAT No GB310392051